Tahiti’s whale-watching tourism is drawing crowds with spectacular sightings, but it’s also raising concerns about the impact on these majestic creatures.

A giant whale stole the show at the Summer Olympic Games, shooting out of the water as athletes competed in women’s surfing semi-finals on the French Pacific island of Tahiti last month. It is for spectacular scenes like this that many tourists travel each year to French Polynesia, one of the world’s prime destinations to go whale-watching and even swim with the huge mammals. But even if the French overseas territory seeks to promote eco-friendly tourism, environmentalists and some scientists warn that growing numbers of travellers present a threat to the majestic species.

Every year, between July and November, humpback whales travel from their breeding grounds in Antarctica to the balmy waters of French Polynesia to mate and give birth, covering the extraordinary distance of roughly 6,000 kilometres (3,728 miles). Located in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean and consisting of 118 islands, the picture-perfect territory known for its crystal-clear waters, stunning beaches and lush landscapes is one of the few places on Earth where tourists can swim with the whales.

“We’re lucky to have humpback whales that come close to the reefs in search of rest and calm,” said Julien Anton, a guide for Tahiti Dive Management, a government-approved operator offering whale-watching tours. “The females try to escape the males, so they come to protect themselves and swim regularly along the reefs.”

Whale song

Humpback whales were decimated by commercial whaling in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Due to conservation efforts and a moratorium on commercial whaling adopted in 1986, the population has increased to around 80,000 individuals. Humpback whales are known for their aerial displays known as breaching as well as elaborate songs with which males court females.

Adult females average 15 meters in length and weigh up to 40 tons, while adult males are slightly smaller. For many Indigenous peoples across Polynesia, the marine animals are sacred. In March, Indigenous leaders from across Polynesia including Tahiti, Tonga, Hawaii, New Zealand and the Cook Islands signed a declaration recognising whales as legal persons with inherent rights.

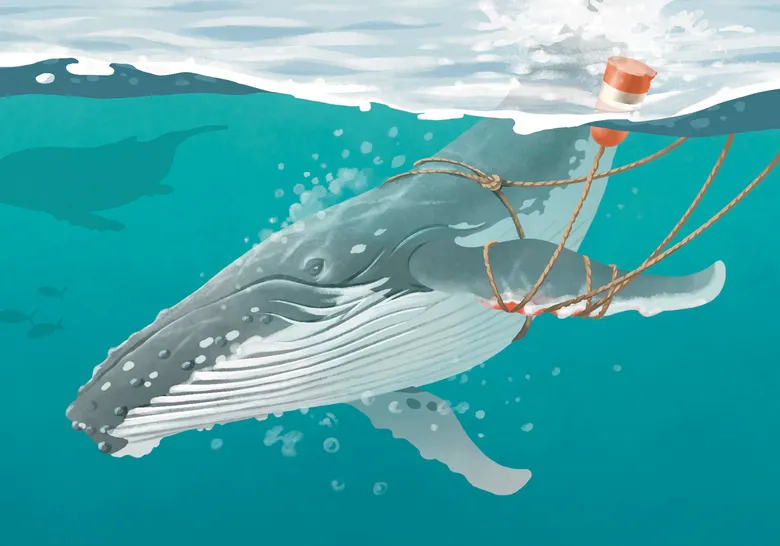

They hope that the move would strengthen the protection of the species, which is under threat from climate change, ship strikes and whale watch harassment, among other risks. Whale-watching is an important source of income for French Polynesia, and authorities have taken steps to promote responsible tourism to protect the cetaceans.

In April, regulations imposed a safety distance of 100 metres between the animal and authorised boats, while swimmers must stay 15 metres away. “This is one of the last places on the planet where we are allowed to observe them at such close quarters,” said Anton.

‘Do it with love’

However, environmental associations and some scientists have criticised the boom in whale-watching activities. The Polynesian association Mata Tohora, which works to protect marine mammals, says there are far too many boats on the water. “We need to limit the number of boats around the whales and dolphins. It’s a question of managing the activity, which needs to be done quickly,” said Agnes Benet, a biologist and founder of the association.

“You can swim with the whales without disturbing them,” she added. “It’s possible if you take the time, if you’re patient and if you do it with love.” Her association is campaigning for the introduction of a “no whale-watching” period, from 2:00 pm onwards, to allow them to rest. A study carried out in the South Pacific island nation of Tonga and published in the journal PLOS One in 2019 pointed to “detrimental effects” on the whales targeted by swimming activities, especially mother-calf pairs.

The study said that both observing and swimming activities cause “avoidance responses” from humpback whales, with mothers diving for longer periods of time in the presence of vessels and swimmers. The risks are not limited to the animals. In 2020, a 29-year-old female swimmer was seriously injured off the coast of Western Australia after becoming trapped between two whales.